Pianta

The whole of the Sala Capitolare is lined with walnut panels enclosed between unusual allegorical sculptures made by Francesco Pianta between 1657 and 1676.

The sculptor himself has supplied us with titles and descriptions of his works, which he calls ‘hieroglyphs’, in the long scroll held by the statue of Mercury on the left of the staircase doorway. The ensemble constitutes a moralising iconographic programme, based on the counterpointing of vices and virtues, ending with a homage to the arts of sculpture and painting.

Following the order indicated by the sculptor the sequence begins with the allegories positioned under Tintoretto’s Adoration of the Shepherds, and continues clockwise. The series of allegories opens with Melancholy, represented as a man with a lugubrious expression and long wavy hair, and wrapped about with a loose cloak. In the space between this figure and the next, representing Honour, seen as a handsome young man with delicate features, equipped with a flag, a necklace and a sceptre, the sculptor has introduced an elegant decorative panel with an empty frame surrounded by carved decorative flourishes, following an alternating scheme that will be repeated along the wall.

Avarice, the uncontrollable desire to possess, is an austere figure with a flowing beard, carrying ledgers and money bags under his belt. Ignorance follows, showing a marked realism in a near-caricatured face of bestial ugliness. Science is pictured as an old man intent on reading the book open on the lectern in front of him. The sixth allegory, a naked young man seen from behind, is one of the most unusual and difficult to understand. It is labelled the Distinction between Good and Evil. Once again the sculptor’s virtuosity is evident in the realism of the character’s attributes.

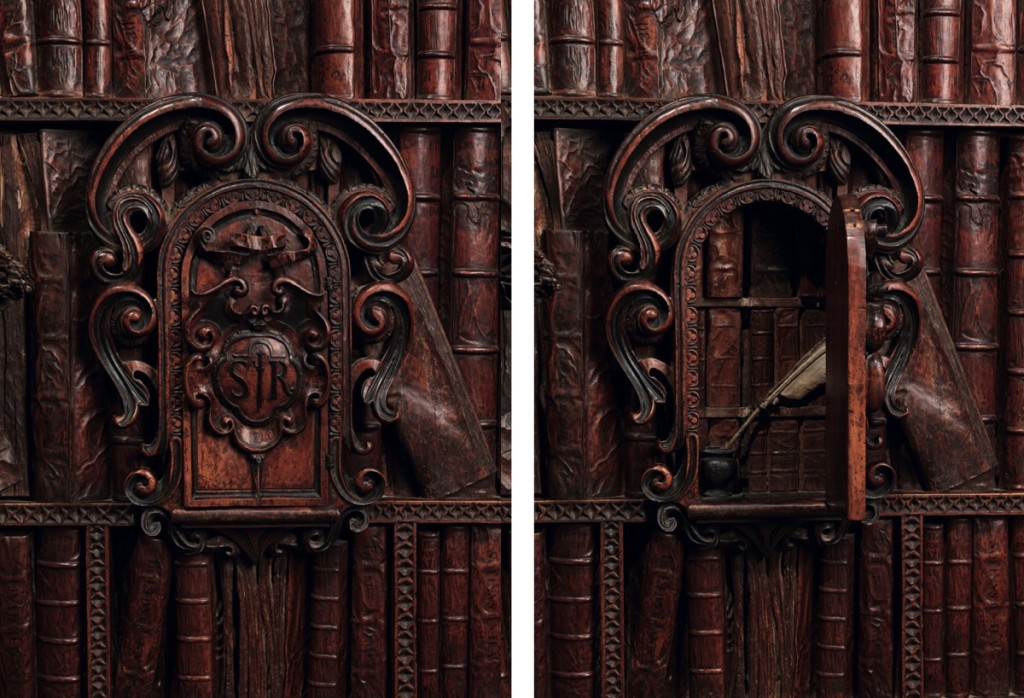

Between the winged Fury, chained and blindfolded, one of the liveliest sculptures of the series, and Curiosity with its covered face, opens the bookshelf with its five shelves stuffed with books (64 of them!), an absolute masterpiece of wooden sculpture for its detailed realism in the rendering of each element: the books, the reading glasses propped on the book at the bottom, the quill with its inkwell.

Scandal and Scruple is a bearded old man, elegantly attired. The musical instruments at his feet indicate that he neglects the serious things in life in favour of the vain. But he is also Scruple, and fears the judgement of God. Honest Pleasure is a fine-looking young man, with long hair.

The task of arguing for the importance of Sculpture falls to the great orator Cicero. A strong realism characterises his face and is particularly evident in the truncated foot in the foreground, which is intended by Pianta to demonstrate how sculpture is mainly admired with the eyes but can also be judged by touch.

The allegory of Painting, which is signed with Francesco Pianta’s full name in a long inscription, is the last one he made on this wall, whose wooden panels close with a pair of Caryatids standing at the sides of a carved frame, perhaps the result of an 18th-century restoration. As Pianta himself indicates, the defence of Painting must obviously be embodied by Tintoretto, portrayed by the sculptor with an intense realism bordering on caricature. The sculptor’s extraordinary command of detail can again be seen in the rendering of the painter’s working tools.

Of slightly lower quality with respect to the facing wall, possibly due to the intervention of assistants, the wooden panels proceed on either side of the doorway onto the stairs up to the Treasury and on the left and right of the doorway into the Sala Dell’Albergo. In the closing passage of his long explanation of his ‘hieroglyphs, Francesco Pianta refers to those “under the windows”, and even to the detail of the intaglio on the decorative panels between which are now set the eighteenth century wooden statues of Faith, Hope and Charity by Francesco Bernardoni, which would seem to confirm the hypothesis that these substitute what ought to have been Sculpture, Truth and Painting according to the original scheme. This also goes towards explaining the presence of the so-called Hercules between the windows. We do not know if the three planned figures were made, but later replaced, or whether this part of the panelling was only completed in the eighteenth century, changing the subjects. It cannot be excluded, in fact, that, in completing a cycle left unfinished, the Scuola had taken the opportunity of reaffirming the religious significance of the Sala Capitolare, from which Pianta’s eccentric allegorical sequence might seem to have strayed.